Evaluating Cognitive and Adaptive Skills in AGS: Insights Beyond Motor Impairments

Many AGS children have normal nonverbal IQ

You've been saying it for years, and now we have proof. Even though children with Aicardi-Goutières Syndrome (AGS) have serious problems with movement and speaking, many score normally on intelligence tests that don't require talking. This shows that nonverbal cognitive skills in children with AGS are often strong, highlighting their true potential.

Understanding Cognitive Abilities in Children with AGS

To understand the thinking and learning abilities of 57 children with AGS, a study used tests that measure cognitive skills without relying on speech or movement. Scores were compared with the severity of a child’s condition and with how parents view their children's skills and adaptive behavior.

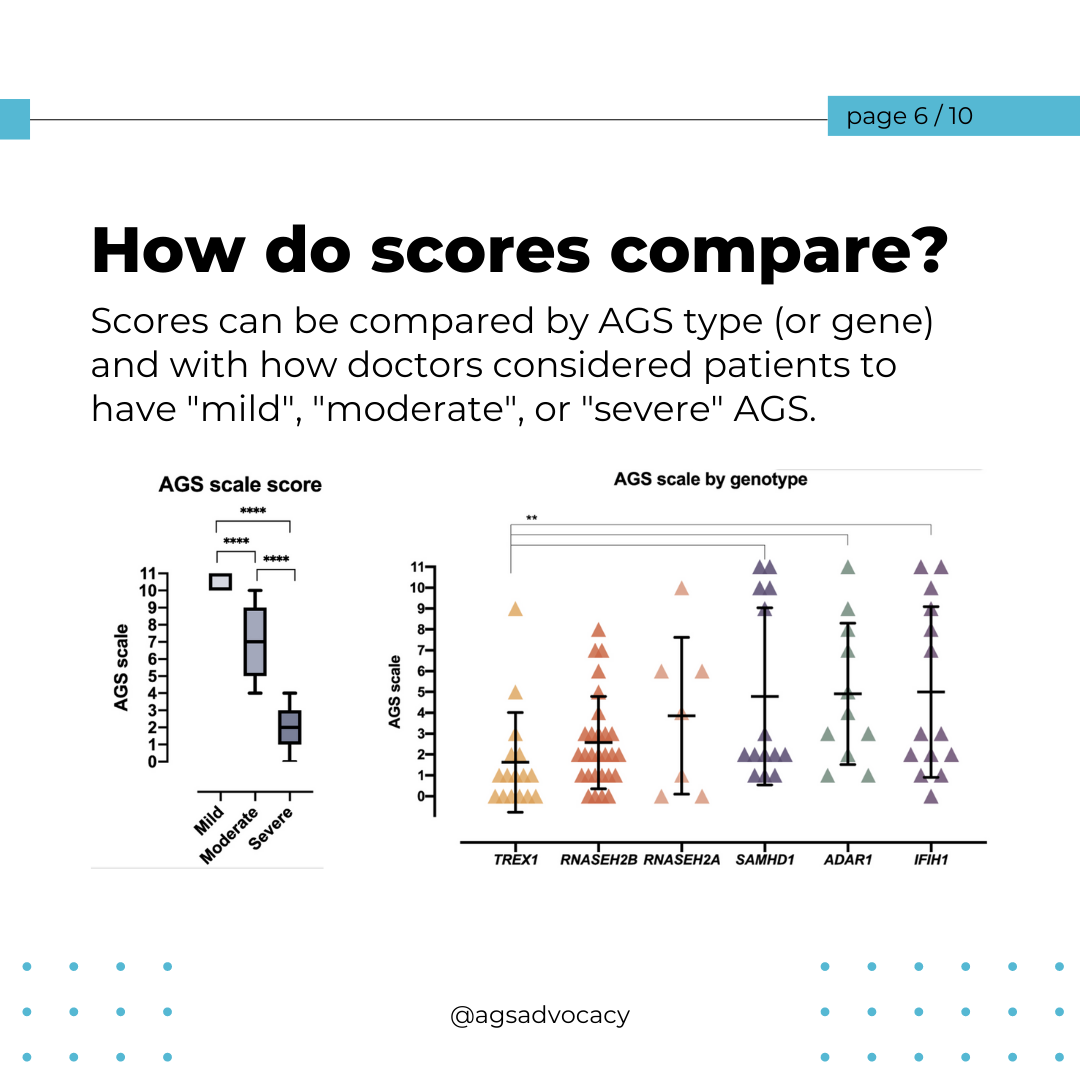

AGS Severity and Cognitive Skills

Overall, tests showed that motor skills were the most affected, while communication, daily living, and social skills were less impacted in children with AGS. The severity of AGS was strongly linked to scores for thinking and everyday abilities.

Intelligence Despite Severe Motor Impairments

Some children with AGS scored within the normal IQ range despite severe physical disability. "Within each gross motor and fine motor category of the AGS Scale, a subset of children scored within normal IQ range." This suggests that cognitive abilities can vary widely among children with similar motor impairments.

Parental Assessment and Performance Measures

The study also demonstrated that parents' evaluations of their children's abilities matched the actual test results. This correlation shows that parents' views align closely with professional assessments of how well their children perform in various tasks.

Enhancing Understanding with Better Assessment Tools

The VABS-3 and Leiter-3 provide deeper insights into children with AGS, beyond just their motor skills. This helps us understand their abilities better, design effective support, and plan clinical trials. By doing so, children can achieve their full potential in communication, education, and daily life, paving the way for a brighter future.

Key Takeaways

Presume Competence: Always believe in the abilities of children with AGS. They can often understand and learn more than it might seem at first.

Personalize Support: Using these assessment tools, clinicians and educators can create tailored support plans that focus on each child's strengths.

Encourage and Celebrate: Recognize and celebrate every achievement, no matter how small. Positive reinforcement can boost confidence and motivation.

Stay Positive: A positive outlook can help families and support teams encourage children to reach their full potential.